What Am I So Afraid Of?

After years of looking at every opportunity as a chance to fall flat on her face, Valerie Monroe learns to grab life by the banister.

As a French major in college, I had the opportunity to work as a nanny for a wealthy French family. I don't remember the details exactly, but I do remember that they lived in what seemed like a palatial townhouse in Manhattan, had several homes in Europe, and planned to spend the summer traveling, child—and nanny—in tow. Whatever the difficulties or challenges of accompanying this particular family might have been, the chance to travel widely throughout Europe was not only exciting but also unavailable to me any other way at the time. Plus I adored kids, and was planning to teach. It seemed a great fit. And yet I was afraid to take the job, afraid the family wouldn't like me, afraid I would be lonely, afraid I wouldn't be able to care for the child well, afraid I'd miss my boyfriend and my family. So I stayed home that summer, living in my parents' house and working in an office at a perfectly nice, decently paying, perfectly boring job. To keep myself amused, I read novels set in Paris and Venice, wondering what it would be like to go there. Time after time in the years that followed, various opportunities shined on me, lighting the way to potential adventure, but my fearfulness stretched out before me like a shadow, dimming the prospects.

The strange thing is, if I were thrown into a situation in which there might actually be something to be afraid of—a sinking canoe, to choose a random example, or a building fire—I know that I would deal with it well, not lose my head or become paralyzed with anxiety but take care of business, be effective in the moment. I've handled things that prompted people to say, "That must have been incredibly scary," though I didn't feel overwhelmingly afraid at all. What, then, is the nature of my fearfulness? If I had to give it a name, I would call it "What if...," because it derives all its power from the possibilities of what might happen at some point in the future and not what's happening right now.

I can see how What if... might have been more useful a long time ago. In fact, I remember considering the idea of sliding down a banister in the house where I grew up—I must've been around 3, because the banister seemed very high off the ground—and thinking, "Fun! Long ride! Fast! New!" Then: "But what if when I get to the bottom, I fall off the end?" Which I certainly would have done had I followed through, with painful and injurious results. The trouble is that somehow as I matured, asking What if... became a way of introducing every possible disaster that could happen, no matter how unlikely. Falling off the end became, in my mind, a probable result even when it wasn't. And thinking about that, I began to want to avoid asking the question because it evoked so much anxiety. So I sought the comfortable and the familiar rather than the exciting and the exotic. It was easy, it was even joyful and delightful (as the comfortable and familiar can be), but it was rarely challenging in a way that leads you to live your fullest life.

A while back, I was offered a job. Supported contentedly by my freelance writing work, very cozily ensconced in my flexible schedule, I didn't think I'd be interested in a full-time position that would require me to show up at an office every day. But: I was an avid reader of the magazine (the one you're reading) where the position was available; I had deeply admired the talent and integrity of the staff; and the job required that I learn about a field—the beauty industry—about which I knew very little. All positives. And yet. I was afraid to take it, afraid the staff wouldn't like me, afraid I would be lonely, afraid I wouldn't be able to do the job well, afraid I'd miss the ease and familiarity of my freelance life. I recognized it as the same fearfulness I'd felt more than 50 years ago, playing out in a different way. When I thought of the possibilities that might come with the job—Fun! A long ride! Fast-paced! New!—my heart leapt. But of course, then: What if...? The leaping turned to pounding. This time, through the racket, I simply said yes, I'll do it. It finally seemed more painful not to take the risk than to take it. If I fell off the end? I'm a big girl now; I thought I could handle it. I imagined my fearfulness as a scrim fluttering between me and the unknown. I would try walking through it.

On my first day at the office (after a sleepless night), I expressed my anxiety to one of my new colleagues. "I'm really scared I'm not going to be able to do this job," I told her. "I feel as if I don't know anything about anything."

"And if you can't do it?" she said.

"Then," I said, "I guess I'll slink out of here in shame." She seemed to understand the depth of my unease without making me feel that it was justified. Then she patted me on the arm. "It's always good to have a plan," she said.

When I submitted my first shot at a photo caption (just a caption!), it was quickly returned to me with "cliché" scrawled across the top of the page. Yikes! I had my plan, of course. But slink out in shame? I didn't think so. At least not without another try. And—damn!—another. Finally: "perfect." In 30 years, I've never had a job I've enjoyed more, that has pushed me more or offered richer opportunity. The possibilities I thought might materialize are even more interesting, more exciting than I'd imagined. I'm still butting up against fearfulness at almost every turn. But now, when it feels right, to the din of my pounding heart, I walk through it.

Life Isn't A Beauty Contest

After years of judging her looks, Valerie Monroe finally figures out a way to end the competition.

I grew up with a Barbie doll. Not a toy—a mother. She was a model, raven-haired, green-eyed, statuesque, with unrealistically perfect proportions, but there they were. Like the doll, my mother had an extensive wardrobe; Mom's even included a couple of mother-daughter outfits. Were they fetching? I don't remember. I do remember gazing at the two of us dressed alike: one, a full-blown goddess, larger-than-life, a voluptuous Renoir; the other, a skinny, freckle-faced tadpole, an anonymous, unfinished pencil sketch. It was in the shifting of that gaze—Mom, me, me, Mom—that my comparing mind was born. As far as my appearance was concerned, I was undefined except in relation to another woman. Whereas my mother was full and round and complete, I was thin, angular, inchoate. My mother's hair was wavy and thick, always perfectly coiffed. Mine was straight and fine, my bangs always uneven. Clothes clung languidly to my mother's curves like an exhausted lover. My clothes, like worn-out Colorforms, refused to stick to me; elastic waistbands were sewn into my skirts to keep them from falling down.

Though today I'm no Renoir, neither do I have trouble keeping my skirts up: It's a 51-year-old body I live in. I've finally matured. But my comparing mind has not. It's stubbornly stuck at 6, and if I were to follow its voice, I would feel once again like a tadpole among women. Though I'm full-grown, in my comparing mind I almost always come up short. So when it clamors to be heard, I listen as I would to a recalcitrant child, and then quiet it.

Here's what I mean: As I'm walking down a crowded city street, a gorgeous young creature in her thirties, sleek and glossy as a black cat, crosses my path. "Bad luck for you!" cries my comparing mind. "You'll never look like that again! You're old and invisible!" The woman and I are stopped at a curb. Her beauty imbues her with a mild haughtiness. In a regal kind of way, she turns her head in my direction. I catch her eye.

"You," I say, "are simply magnificent."

The haughtiness vanishes instantly. She's a bit taken aback, momentarily scrutinizes me for motive, sees none apparent, and then smiles her wide (magnificent) smile. "Why, thank you," she says.

"It's my pleasure to tell you," I say, and it is. Because I not only remember how happy I have felt as the recipient of an authentic compliment, but now I have enjoyed the additional gratification of being able to give one. Though my comparing mind wants to nullify my power and kick me off the playing field because I can no longer compete, the power I have today is irrevocable. After years of passively accepting a definition of beauty other than my own, of striving to be a noticeable object, I've now assumed an active role, too: Appreciator of All Things Beautiful.

There are several things that recommend the role of appreciator. It's easy to be very busy—at least as busy as one can be striving to be among the appreciated. I've discovered what the smartest men have always known: that women can be lovely in many ways—as many ways, it seems, as there are women. It's easy to be very happy, noticing things to admire rather than looking only for ways to be admired. You know that feeling you get when you see a lush summer garden, abundantly green and fragrant and riotous with blossoms? Does it bother you that you're not as beautiful as it is? No, of course not; it's a garden. Its beauty has nothing to do with you, takes nothing away from yours. In fact, standing in the middle of a flourishing garden, filling your eyes with the deep and impossibly delicate colors, inhaling the odors, sweet and complex, you might feel more beautiful, more precious yourself, marveling at your own ability to perceive it all. That's the way I feel about those women I used to think of as competitors: Their beauty is one more avenue for a rich enjoyment of the world.

But maybe most important as an appreciator, I'm setting my own standards. Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? No, I won't. I won't compare you—or myself—to anything, not the weather, not our mothers, not that gorgeous creature crossing our paths. Because a thing of beauty needs no comparison, only an eye to behold it.

Hi, Sweetie

The mirror reflected a face Valerie Monroe could love—her own.

My mother will vociferously disagree, and I am happy to let her, but: I am not a beautiful woman. I won't bother to bore you with the details, though I can give you an idea of what I mean. Recently I had the experience of being photographed next to the model Iman, arguably one of the most gorgeous women in the world and certainly the most gorgeous woman who has ever stood next to me in a picture. When a friend kindly (or unkindly, I'm not sure) sent me a print, I was struck by how different we looked. We're about the same size, she and I, not too far apart in age, and it was a close shot of the two of us talking, face-to-face. As I stared at the photo, I saw two flowers: Iman, an exquisite hothouse orchid, her exotic beauty in full, outrageous bloom; and me, a parking-lot daisy, still standing, firm but a little faded, late on a warm afternoon. I got a slightly disappointed feeling, looking at that photo, like the feeling you might get opening an unexpected bouquet to discover that the flowers are a day old. So I went over to the mirror to check in with myself. I took a good, long look. Then, "Hi, sweetie," I said. I felt enormously better. Because even though there are many women in the world much more beautiful than I, I love my face.

It wasn't always so. If you had asked me 20 years ago what I thought of my face, I would've said, "It's fine," in the same way you answer someone you don't know very well who asks how you are. Nothing to complain about. But the whole truth was, when I looked in the mirror, I saw someone who was most of all not-quite-as-pretty-as.

Then I got married, and then my husband began to have some serious problems that resulted in both of us reexamining our lives. For several years I worked hard with a therapist to come to an understanding about how I had grown into the person I was, and how I might recapture the parts of myself that I had once loved and lost.

One day, after I was being particularly self-critical, my therapist suggested that I spend some time—as much as I could take—looking in the mirror, not the usual way, but looking into my eyes in the way I might look into the eyes of someone I cared deeply about. Have you ever tried this? It isn't easy. It feels creepy at first, as if you're putting the make on yourself. But I diligently watched as I laughed (out of nervousness). I got teary-eyed (fear, I think). And then I saw myself. Standing at the mirror, looking into my own eyes, I finally saw the human being who looked out of them.

I recognized her, of course. Because I knew her intimately, knew everything about her struggles and her achievements, her aspirations and her disappointments, because I knew that she was, above all, well-intentioned and kind, I loved her. And seeing her face—my face—like that of a beloved friend's, always reminds me of that.

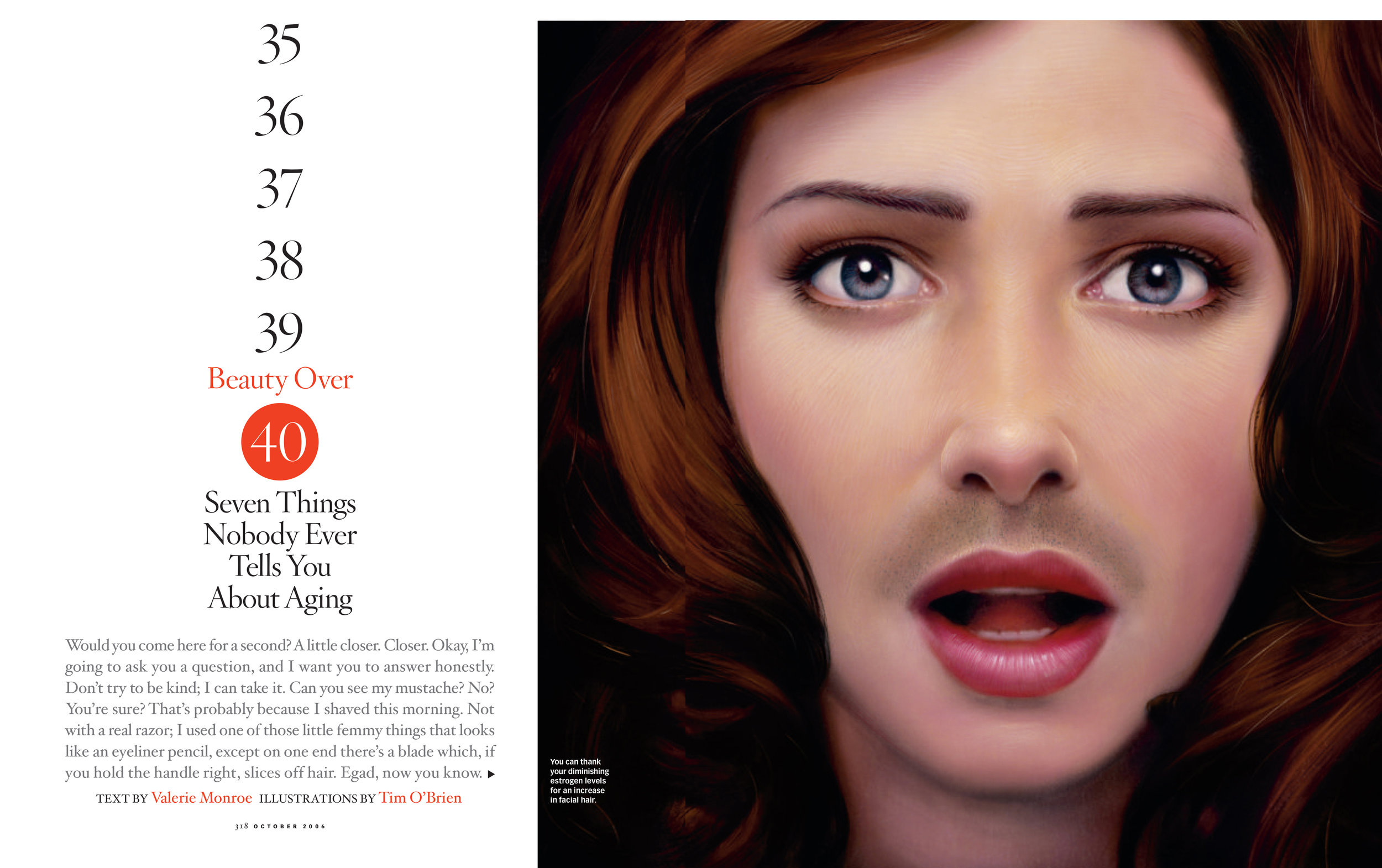

Seven Things Nobody Ever Tells You About Aging

Would you come here for a second? A little closer. Closer. Okay, I'm going to ask you a question, and I want you to answer honestly. Don't try to be kind; I can take it. Can you see my mustache? No? You're sure? That's probably because I shaved this morning. Not with a real razor; I used one of those little femmy things that looks like an eyeliner pencil, except on one end there's a blade which, if you hold the handle right, slices off hair. Egad, now you know.

If, like me, one of your aspirations is to one day be, by any measure or evaluation, really, really old, you're most likely going to have to deal with more than a mustache. You will probably get a full coat of down on your face, and a long stray hair here and there on your chin. The hair on your head will probably get thin, as will your eyebrows and eyelashes. (Oh, I nearly forgot—your pubic hair, too.) You'll get spots on your hands and bunions on your feet. Your nose and ears may appear to have grown out of proportion to your face. And that expression "long in the tooth" will endearingly apply to you: A receding gum line will make your teeth look bigger...I still can't believe you're reading this. There's a lovely picture of a young woman posing in a pretty suit on page 322; wouldn't you rather go there? Okay, as long as you're staying, I'll tell you how you can look beautiful as you age. Or at least how not to look like a man.

1. You Start to See More Hair on Your Face

Here's why you have more of it than you did when you were 20: hormones. Though a significant minority of women of all ages have coarse dark hair growing on their chin and upper lip because of a genetic predisposition, most women who have excess facial hair have an underlying hormonal issue, says Doris J. Day, MD, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at New York University Medical Center. As we age, our bodies lose estrogen; testosterone, unopposed, causes us to grow more hair where men have it, on our faces (and to grow less on our heads).

If you occasionally have several dark (or white) hairs on your lip or chin, it's fine to whack them off with a razor; plucking isn't the best option, because the force of the pluck can irritate and leave a bump, says Day. A couple of staffers here at O have female relatives who shave their faces; most dermatologists don't recommend this for several reasons, among them the fact that the down on your face feels soft because it's been there for a long time; shave it off, and it's going to grow back stiff or coarse (though no thicker than before). Laser hair removal works only in certain situations, says Loretta Ciraldo, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami. It's not effective on white hair, and if your skin is olive or darker, laser can cause postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which looks like a dark stain, so it could leave you with something like a mustache even though there's no hair on your lip. Electrolysis—a procedure in which the follicle is destroyed by heat through an electrical current—is a good solution for stray hairs, says Ciraldo, but it's not good for large areas. The prescription cream Vaniqa inhibits the enzyme that hair follicles need to grow. Ciraldo advises applying it twice a day at first; if the hair stops growing within three months, she then suggests application once a day, followed by every other day, to determine the minimum amount needed to prevent recurrence of growth. She says that most of her patients find that Vaniqa gets rid of all visible hairs.

Ciraldo also points out that she can't see the facial hair on 75 percent of the women who complain to her until she's within a few inches of their faces. She attributes their concern—and I'd say, considering personal experience, that she's right—to magnifying mirrors. In an unlucky confluence of events, just as our eyes start to go and we need a magnifier to apply makeup, we start getting more facial hair. So stand at arm's length in front of a regular mirror, she says. If you can't see the hair on your face, you don't need to do anything about it. (Gosh, I hope I'm right that you can't see the hair on my face from arm's length, but I get rid of it anyhow in case I want to encourage someone to come in for a close-up. That seems reasonable, doesn't it?)

Being downier can present an unattractive problem with makeup. "Peach fuzz on the face can 'grab' powder and foundation," says Maria Verel, celebrity makeup artist. There are a couple of tricks to prevent that. Apply foundation the way you apply moisturizer: Rub it in and let it set (or dry), says Verel. Then buff it off with a cloth or a clean, slightly damp sponge. If you also wear powder (or a powder foundation), after application, lightly mist your face with water to settle the powder. You can just let that be, or pat it dry.

2. The Hair on Your Head Starts to Thin

Hold on to your hat before you read this disheartening statistic: Fifty percent of postmenopausal women have noticeable thinning of the hair on their scalp. After age 50, approximately the same number of men and women suffer from thinning, says Ken Washenik, MD, PhD, medical director at Bosley, a surgical hair restoration medical practice, and clinical assistant professor of dermatology at New York University School of Medicine. The reason, again, is most likely loss of estrogen, which is protective of hair. You shed some hair naturally every day, but the loss is considered significant if you start to see thinning behind the hairline or your part is widening.

Washenik says the first thing to do if you notice thinning is to see a doctor, who can determine whether it's the result of a correctable condition (an overactive or underactive thyroid or low iron levels, for example) or medication (such as for high blood pressure or depression). If there's no underlying cause except age, Washenik recommends minoxidil (Rogaine) 2 percent. (Rogaine is available at 5 percent for men only; the FDA hasn't tested it or approved it at that strength for women.) Thinning hair has a shorter anagen (growth) phase than normal; that phase typically shortens as we get older. Minoxidil extends the growth phase. Apply it to the scalp at least once a day; if in three months you see no difference in thickness, it's not going to be effective. Minoxidil is a chronic maintenance therapy, which means that if you stop using it, it stops working.

As for styling, don't overload hair with product, because that will weigh it down, says Stephen Knoll, owner of the Stephen Knoll Salon in New York City. Overcompensating with too much volume results in thinner-looking, cotton candy hair, so go for a sleek style, he says. And avoid parting your hair in the center; an uneven side part will make your hair look fuller. Thickening shampoos can also make hair appear fuller.

3. Your Eyebrows Become Sparse

Are your eyebrows getting patchy? Perhaps you'd like to consider an eyebrow transplant. Or perhaps you wouldn't: In the restoration procedure—which takes two to three hours in a doctor's office—individual hair follicles from the back or side of the head (where they aren't noticeable) are removed and placed into the brow area to re-create whatever density you like, says Washenik. But wait a minute: Why wouldn't the hair grow as long as it would if it were still on your scalp? It does, says Washenik. The transplanted follicles don't know that they've been moved, so you get something like bangs growing from your browbone. To avoid this potentially tragic state of affairs, forget transplants and try an eyebrow pencil or powder. Choose one that's a shade lighter than your haircolor, and with feathery strokes, fill in the patchy areas, says brow expert Sania Vucetaj. Brows grow a little longer as we age; brush them upward and trim.

4. Your Nose and Ears Seem to Be Growing

Looking in the mirror one morning, I noticed this unpleasant surprise: My ears seemed to be larger than they used to be; not a lot, but definitely bigger. Then I started discreetly examining my friends and other older women. Slightly bigger ears on most of them. Was I imagining it? Evidently not. Though our ears are 90 percent grown by age 6, and our noses are almost fully grown by the time we're teens, both do change shape and appear to enlarge as we age. One theory about the nose is that it has a large number of sebaceous glands, which have a high cell turnover rate and therefore growth potential, says Neil Sadick, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York City. But both the ears and nose droop as soft tissue (skin, fat, and muscle) relaxes and structural support changes (bone recedes with time, so there's less foundation to hold the skin and cartilage up), says Alan Matarasso, MD, clinical professor of plastic surgery at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University in New York City. Plus, loss of elasticity and collagen in the skin causes sagging. He's seeing increasing requests for rhinoplasty and earlobe surgery among patients having facelifts. Heavy earrings can stretch the soft tissue of your earlobes; wear light ones. But if you've been hanging major bling from your ears, there's earlobe reduction, an in-office procedure that takes about 15 minutes per ear, requires a local anesthetic, and heals well, says Robert Klausner, MD, medical director at the Center for Cosmetic Surgery in Bonita Springs, Florida.

You can't entirely prevent your nose and ears from drooping, but you can minimize it by following Matarasso's advice: Avoid the sun, smoking, and weight fluctuation, and start using prescription-strength skincare products, including retinoids (which help preserve and regenerate collagen), in your 20s.

5. Your Teeth Become More Prominent

If you're long in the tooth, it's because your gums are deteriorating and have begun to shrink away from the crown portion of your teeth, exposing some of the root, says New York City dentist Marc Lowenberg. The length of the average front tooth is ten to 12 millimeters; with recession, including root exposure, it can become as long as 15 to 17 millimeters. In the same way that our skin loses collagen fibers, our gum tissue loses mass. The best preventive measure is to keep your gums free of bacteria—by brushing and flossing twice a day—because bacteria cause gum disease, which worsens recession. Also, overly vigorous brushing can scrub away gum tissue, so avoid it.

6. Your Hands Are Veiny and Spotted

I love old, veiny, spotted hands. There's something beautiful, very wabi-sabi (the Japanese appreciation of transience) about them. Especially with a big, chunky, burnished pink-gold ring or some other imposing adornment, old hands look to me as if they've earned the right to carry heavy, important jewelry. But if you prefer the soft, plump, unmarked hands of youth, use the same antiaging products you use on your face, says Matarasso. That should include a retinoid, an AHA moisturizer, and—this is critical—sunblock. If you haven't been good about sunblock, you can have hyperpigmentation spots lightened with laser; veiny hands can be plumped up with Restylane, collagen, Sculptra, and fat injections. I'd rather use the money I could spend on rejuvenation on a cocktail ring.

7. Your Feet Are Gnarly

I never tried polish on my toenails till after college—too busy before then rejecting feminine convention—but once I did, looking down at my brightly or delicately painted toes became one of the great little pedestrian pleasures of my life. I try not to wear shoes that strangle my feet, and you should, too, because your feet, breathing easier, will manifest your kindness in their pretty appearance. Eventually, though, we're all going to lose some elasticity and flexibility in the soft tissues—the tendons and ligaments—of our feet, which can lead to increased stress on the bones, potentially causing them to change shape. And when the bones start to change shape, you're looking at hammertoes and bunions. (All right, don't look at them, but there they are.) A tight Achilles tendon from years of wearing high heels can predispose you to such foot problems, says John Giurini, DPM, associate clinical professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School. So don't wear heels when you don't have to, he says. Also, stretch your Achilles tendon and the plantar fascia (the ligament that runs from your heel to the ball of your foot), wear supportive shoes, and if your feet are hurting, consider getting a doctor's evaluation—orthotics can prevent ugly problems from worsening. Orthotics? Take my hand. It won't be easy, but we'll hobble through this together.

6 (More!) Things Nobody Explains to You About Aging

Are those leopard spots on your face? Why does your hair suddenly feel so brittle? ...And is that a turkey wattle? O's beauty director makes sense of it all.

Several years ago I wrote a story called 7 Things Nobody Ever Tells You About Aging. Lots of you commented on it. So the editors at Oprah.com thought it would be a good idea for me to write a kind of addendum to it. Something like "6 More Things Nobody Ever Tells You." "It'll be easy," they told me. "You won't even have to do any research." By which they meant that I could look back into the beauty story archives and pull out those pieces that had to do with specific challenges to your looks as you age. (And by which they didn't mean, as I immediately thought, that all I would have to do is to gaze down at my 60-year-old body to discover "6 More Things Nobody Ever Tells You." They didn't mean that. They swear it.) So here are six more decrepitudinous things you either have to look forward to if you're lucky enough to make it into your fourth, fifth, and sixth decades and beyond, or, well, if, like me, a glance in your mirror tells you unequivocally that things they are a-changing.

1. You may develop "turkey neck"

Why: The skin around the neck is particularly prone to the wear and tear of aging because it's thinner than facial skin and has a different collagen content, says Alan Matarasso, MD, clinical professor of plastic surgery at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. Plus, it's one of the most sun-exposed parts of the body, making it especially vulnerable to UVA/UVB damage.

What to do about it: You can take preventative measures by using the same prescription or prescription-strength products on your neck that you apply on your face, including retinoids (such as Retin-A, Renova, or Tazorac), and, of course, sunscreen every day.

But the problem with turkey neck is that once you have one, you can't get dramatically improved results without taking dramatic action. Think of your neck as a skirt that needs hemming, suggests the metaphorically gifted Matarasso. You can iron the skirt (meaning treat it with various lasers, which can help smooth the skin) and reinforce the fabric of the skirt (meaning apply creams like retinoids that will encourage production of collagen and elastin), but unless you hem the skirt, you won't lose the excess fabric. What does "hemming" entail? An incision behind the earlobes, suctioned fat, lifted and tightened muscles, and a small scar from behind the ears into the hairline. (Not to mention a recovery time of 10 to 14 days, and a cost of about $10,000.)

Bottom line: If your turkey neck is in full swing, neither lasers nor creams will make an appreciable difference. However, before you send your neck to the tailor, think long and hard about what people see when they look at you. Your magnificent eyes and delicious smile may render your neck way less noticeable than you think.

2. Your hair gets frizzier and more brittle

Why: As we age, our scalp can become drier, which can make the hair drier, too; and when hair loses its pigment, turning gray or white, its texture often becomes frizzier, says David H. Kingsley, PhD, a board-certified trichologist.

What to do about it: Your hair needs moisture, and the best way to restore it is with a moisturizing shampoo and conditioning treatments. Use a leave-in conditioner daily and a deep-conditioner or a thick hair mask once a week (Oprah's longtime stylist, Andre Walker, launched a Keratin Mask and Treatment Pak that you can leave on for five minutes in the shower). Make sure you also eat well and regularly; include enough protein in your diet; exercise; drink enough water (so that you're not thirsty); and to hedge your bets, take a multivitamin, says Kingsley.

Bottom line: Maintaining a healthy diet and keeping your hair well moisturized will make it look healthier and shinier no matter what your age.

3. You're more prone to facial redness

Why: Those great beach vacations you took in your teens are showing up on your face: You're beginning to see cumulative sun damage in the form of blotchiness, red spots, and ruddiness. Menopause can also cause a multitude of skin problems, including extreme dryness and rosacea.

What to do about it: To tone down the pink with makeup, start by applying a lightweight moisturizer with sunblock. On top of that, apply a silicone gel primer over your entire face, says Tim Quinn, Giorgio Armani Beauty makeup artist. (The primer creates a smooth surface for foundation.) Then blend a very small amount of green—yes, green—concealer over the areas that are most pink (try Physicians Formula Mineral Wear Concealer Stick). Finally, with a brush—because it gives you the best coverage—apply a yellow-based, long-wearing foundation. (Quinn says Giorgio Armani UV Lasting Silk Foundation in shade 4.5 flatters almost any skin tone.)

Rosacea can be treated with topical antibiotics—such as MetroGel and Rosac, oral antibiotics and lasers. If your biggest problem is broken blood vessels, usually two to three treatments with either the KTP, pulsed-dye, or diode laser will zap your veins, says Roy G. Geronemus, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the New York University Medical Center. But, if you have rosacea, remember to avoid triggers that induce flare-ups, including the sun, stress, alcohol (especially red wine), spicy or thermally hot foods and drinks, and even exercise, says Jeanine Downie, MD, coauthor of Beautiful Skin of Color. (She advises patients to drink ice water when they work out, to cool the face.) It also helps to use gentle products and to avoid irritating your skin by scrubbing.

Bottom line: You can tone down the redness with a mix of lasers, oral and topical treatments and makeup, but if you have rosacea, avoiding your triggers is a must.

4. You may start to see spots

Why: Age spots can be either light (hypopigmentation) or dark (hyperpigmentation), says Wendy E. Roberts, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at Loma Linda University, and both are caused by sun damage and excess melanin in the skin.

What to do about it: To prevent age spots in the first place, wear an SPF of at least 15 every day. If you already have hypopigmentation, a self-tanner can help blend the spot into your complexion. If you've got hyperpigmentation, apply a topical prescription bleaching agent like Solagé (2 percent mequinol) directly to the spots, which will fade them gradually. A hydroquinone cream also inhibits melanin production—at prescription-strength (4 percent), it should fade darkness in four to eight weeks. An over-the-counter (2 percent) cream takes at least eight to 12 weeks. However, the most effective way to get rid of them is with a laser treatment—either the Q-switched ruby or alexandrite, says Anne Chapas, MD, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at NYU School of Medicine. It leaves a small scab where the spot was, but this disappears in a couple of weeks. Generally one or two treatments are needed, at $400 to $700 per session. If your spots are diffuse (like a Milky Way splash across your cheeks or chest), Chapas recommends the new Fraxel dual laser. One or two treatments, at $750 to $1,500 each, should do the trick. (And for that kind of money, let's hope so.)

Bottom line: Unless you wear a broad spectrum sunscreen every day, rain or shine, you'll be looking at new age spots no matter how often you visit the dermatologist.

5. Your legs start to resemble a roadmap

Why: Maybe you noticed a couple of faint squiggles around your ankles a few years back. Now you see blue lines, like kudzu gone wild, creeping behind your knees, over your thighs. Though no one knows exactly what causes them, visible veins are probably influenced by genetics and hormones. Obesity and standing or sitting for long periods may also exacerbate blood pooling in the legs, which can cause some veins to swell and rise toward the surface of the skin.

What to do about it: If the squiggles are relatively light, a coat of self-tanner will be enough to camouflage them. A leg bronzer will also mask veins or broken capillaries—and wash off at the end of the day. (Yves Saint Laurent Make-Up Leg Mousse imparts both a veil of color and a cooling sensation.) When you want more serious coverage, makeup artist Mally Roncal recommends blending a concealer on top of veins, painting the makeup on with a brush, and then distributing it evenly with your fingers. (Choose something pretty heavy, like Dermablend Leg & Body Cover Creme.) A few pats of translucent powder will set the color, but you'll still want to avoid water sports and games of footsie for the rest of the day.

Want to dissolve that roadmap altogether? The tiniest veins can be zapped with a Vbeam, YAG, or diode laser. The beam destroys the walls of the veins (it will feel like a few quick rubber-band snaps), causing them to disappear within about two weeks. You'll need about three treatments. If the veins are large enough to be threaded with a tiny needle, sclerotherapy—the injection of various solutions into the blood vessels—is the best option, says Tina Alster, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C. The solution irritates the vein's lining and the resulting tissue inflammation causes the blood vessel to collapse and fade. The treatment takes 10 to 30 minutes, depending on the number of veins, and is nearly painless, but you may experience mild redness and swelling along the course of the treated veins. (Avoid sclerotherapy immediately before or during menstruation because of heightened sensitivity.) Expect to pay about $300 to $500 per treatment. Hate needles? You could try vascular laser treatments instead, which are a little more uncomfortable because they zap the veins with heat, says Dr. Alster.

Bottom line: The best time to have treatments for spider veins is in the winter, when your legs are covered and more easily protected from the sun. Tanned skin reduces visibility of the veins during the procedures and increases the risk of post-treatment hyperpigmentation. Be forewarned: You won't be vein-free forever; after a couple of years, new ones will probably form.

6. Your lipstick starts to bleed into the lines around your mouth

Why: I have those lines, and they're called perioral rhytids. And because when I develop something—especially something undesirable—I'm always curious about how it got there, I asked Stuart H. Kaplan, MD, assistant clinical professor of dermatology at UCLA Medical Center, what causes them. He told me: repeated pursing of the lips; sun exposure; loss of subcutaneous fat, collagen, and elastin, which form the structural support of the skin, and of hyaluronic acid, which moisturizes; and genetic predisposition.

What to do about it: As for getting rid of these annoying lines, if you're a smoker, forget it. You don't smoke? Good! But if, like me, some of your favorite ways to pass the time include sucking a thick chocolate malted through a straw, kissing, slurping martinis, and kissing—oh, the louche life of the beauty editor!—you may be fighting a losing battle. On the other hand, you can prevent the lines from getting worse by applying sunscreen to the area between your lip and nose and using a topical retinoid, like Retin-A, Renova, Avage, or Tazorac, which helps build collagen and thicken the skin. If you believe you need the help of a power tool, then an ablative laser treatment, which resurfaces the skin, might be the ticket, says Kaplan. He also suggests injections of small amounts of Botox to prevent pursing, but warns of the risk of losing the ability to enunciate certain consonants. (That's all I needed to hear to reject that option.) Finally, Kaplan suggests the filler Restylane to plump up the creases. Results generally last up to six months.

Bottom line: A good offense is the best defense, so use sunscreen and a retinoid to prevent the lines from getting deeper.

Ask Val: November 2010

Dear readers, this month the "Ask Val" page might better be called "You Didn't Ask Val, but She's Going to Tell You Anyway." Or, more pointedly, "Holy Crow's-feet, I'm Turning 60."

Yes, in a few weeks, I become a sexagenarian—and despite my optimistic nature, I suspect that sounds a lot more promising than it is.

Not long ago, I was trying to explain to a 45-year-old friend what it feels like to be my age. "It's like this," I said. "I'm going to tell you something about yourself that you don't know, and it's incontrovertibly true no matter what else you believe."

"Okay," she said.

I looked at her hard. "You were born in 1950," I said. "You're actually 60." My friend gave me the kind of blank stare you get when something does not compute. "Well, that just doesn't make any sense," she said.

Exactly. The age I am is not the age I feel. And I'm pretty sure that if you're close to 60 or older, you understand the disconnect. It's not uncommon. In a 1995 study of Americans between 55 and 74, most of them felt 12 years younger than they actually were. Studies in Germany and China have yielded similar results.

As you might guess, one of the most important factors in feeling youthful is good health, or at least a sense of control over your health. If you can exercise and generally kick up your heels without throwing out your back or breaking your legs, naturally, you feel more vigorous than your neighbor who has trouble hauling himself out of a chair. It also helps if you spend your days among younger people.

In many ways, feeling younger than your age is a good thing. Research shows that it can have a positive effect on confidence about cognitive abilities (the sort of confidence I could use the next time I search for my glasses and find them on my nose). And people who feel younger than they are, are less likely to die than same-age peers who actually feel that age.

But there's a wrinkle below the surface of this encouraging news.

If you're a woman, when you get to be 60 (or almost) and begin noticing the disconnect between how old you feel and how old you look, you start to think differently about your face. And by "differently" I mean that you suddenly have to make now-or-never decisions about how much control you want to exert over it. You can decide that you want to try to hold on to your youth by any means possible (in which case surgery will be involved). You can decide that you'll only tinker with the aging process, feeling your way day by day (there are copious options, from microdermabrasion to fillers, and Botox). You can decide to say the hell with it, and watch with brave astonishment as a mustache darkly embellishes your upper lip, your eyebrows gradually vanish, and you develop the jowls you fondly remember on your favorite uncle. Whichever route you follow, you have to take responsibility in a new way for your looks.

Did you know that some of the earliest plastic surgery was the reversal of circumcision on Jewish men who wanted to pass for gentile in Roman times? Plastic surgery in this country, too, was often originally about "passing," with immigrants wanting to change their features to conform to the status quo. And isn't it still often about passing? Older women (and men) yearning to pass for younger?

It's lovely if someone thinks I'm not yet 60 (which is happening less often; I appear to be gaining momentum on a downhill run). But I expect that as the body I live in continues to mature, I'll come to accept the duality of looking one age and feeling another—just as I have come to accept other strange and poignant aspects of the human condition, like our awareness of the raw irrefutability of death. It is what it is.

As for my face: I doubt I'll choose to do more than a bit of Botox and a regular flash of skin-toning laser. I've always wanted to look pretty, and I still want to, but age-appropriately pretty. So I'm not going to try to remodel my outside to correspond with how I feel inside. Because, bottom line, I don't really want to pass for anything but what I am.

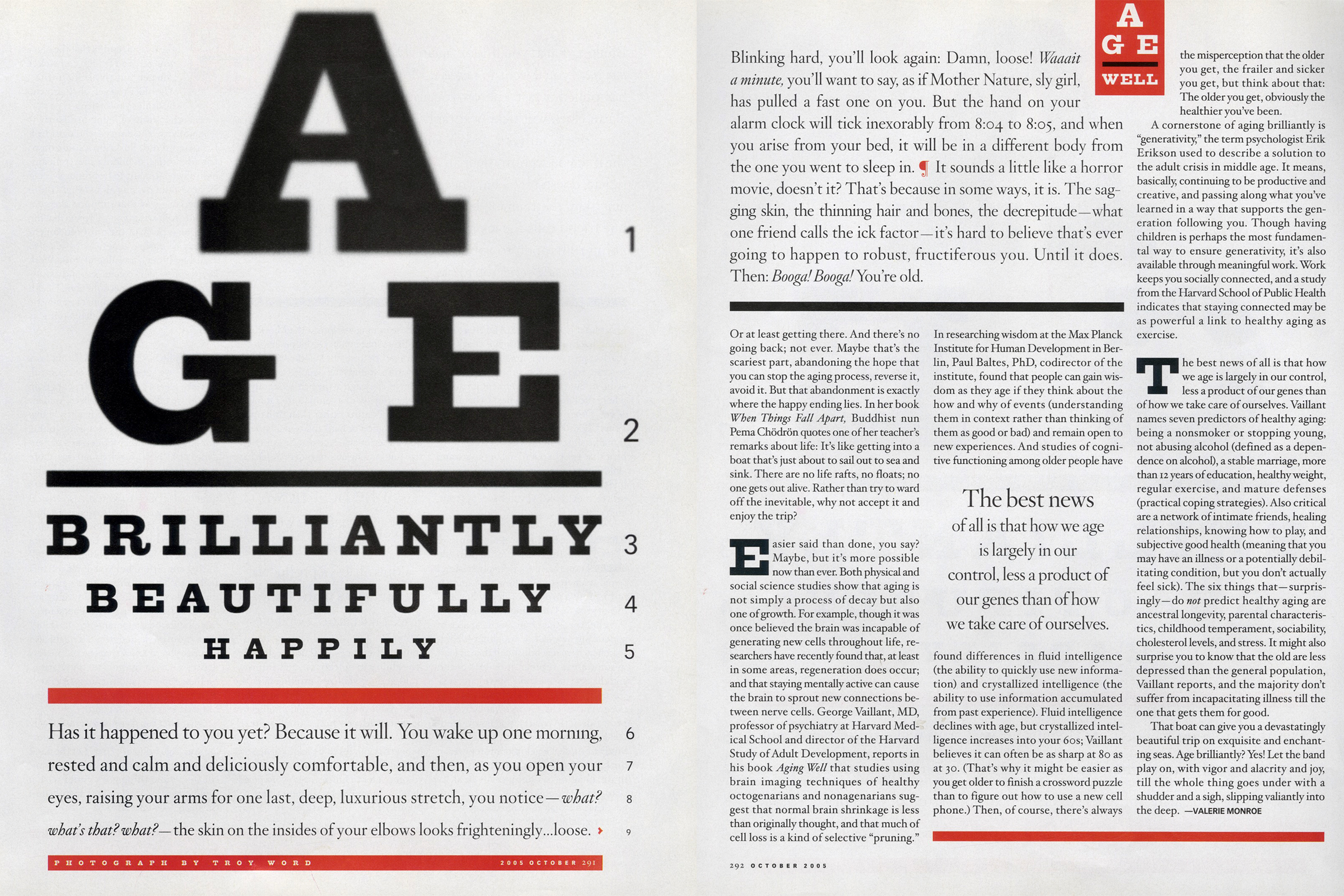

Age Brilliantly Beautifully Happily

Has it happened to you yet? Because it will. You wake up one morning, rested and calm and deliciously comfortable, and then, as you open your eyes, raising your arms for one last, deep, luxurious stretch, you notice—what? what’s that? what?— the skin on the insides of your elbows looks frighteningly...loose. Blinking hard, you’ll look again: Damn, loose! Waaait a minute, you’ll want to say, as if Mother Nature, sly girl, has pulled a fast one on you. But the hand on your alarm clock will tick inexorably from 8:04 to 8:05, and when you arise from your bed, it will be in a different body from the one you went to sleep in. It sounds a little like a horror movie, doesn’t it? That’s because in some ways, it is. The sagging skin, the thinning hair and bones, the decrepitude—what one friend calls the ick factor—it’s hard to believe that’s ever going to happen to robust, fructiferous you. Until it does. Then: Booga! Booga! You’re old.

Or at least getting there. And there’s no going back; not ever. Maybe that’s the scariest part, abandoning the hope that you can stop the aging process, reverse it, avoid it. But that abandonment is exactly where the happy ending lies. In her book When Things Fall Apart, Buddhist nun Pema Chodron quotes one of her teacher’s remarks about life: It’s like getting into a boat that’s just about to sail out to sea and sink. There are no life rafts, no floats; no one gets out alive. Rather than try to ward off the inevitable, why not accept it and enjoy the trip?

Easier said than done, you say? Maybe, but it’s more possible now than ever. Both physical and social science studies show that aging is not simply a process of decay but also one of growth. For example, though it was once believed the brain was incapable of generating new cells throughout life, researchers have recently found that, at least in some areas, regeneration does occur; and that staying mentally active can cause the brain to sprout new connections between nerve cells. George Vaillant, MD, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, reports in his book Aging Well that studies using brain imaging techniques of healthy octogenarians and nonagenarians suggest that normal brain shrinkage is less than originally thought, and that much of cell loss is a kind of selective “pruning.”

In researching wisdom at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, Paul Baltes, PhD, codirector of the institute, found that people can gain wisdom as they age if they think about the how and why of events (understanding them in context rather than thinking of them as good or bad) and remain open to new experiences. And studies of cognitive functioning among older people have found differences in fluid intelligence (the ability to quickly use new information) and crystallized intelligence (the ability to use information accumulated from past experience). Fluid intelligence declines with age, but crystallized intelligence increases into your 60s; Vaillant believes it can often be as sharp at 80 as at 30. (That’s why it might be easier as you get older to finish a crossword puzzle than to figure out how to use a new cell phone.) Then, of course, there’s always the misperception that the older you get, the frailer and sicker you get, but think about that: The older you get, obviously the healthier you’ve been.

A cornerstone of aging brilliantly is “generativity,” the term psychologist Erik Erikson used to describe a solution to the adult crisis in middle age. It means, basically, continuing to be productive and creative, and passing along what you’ve learned in a way that supports the generation following you. Though having children is perhaps the most fundamental way to ensure generativity, it’s also available through meaningful work. Work keeps you socially connected, and a study from the Harvard School of Public Health indicates that staying connected may be as powerful a link to healthy aging as exercise.

The best news of all is that how we age is largely in our control, less a product of our genes than of how we take care of ourselves. Vaillant names seven predictors of healthy aging: being a nonsmoker or stopping young, not abusing alcohol (defined as a dependence on alcohol), a stable marriage, more than 12 years of education, healthy weight, regular exercise, and mature defenses (practical coping strategies). Also critical are a network of intimate friends, healing relationships, knowing how to play, and subjective good health (meaning that you may have an illness or a potentially debilitating condition, but you don’t actually feel sick). The six things that—surprisingly—do not predict healthy aging are ancestral longevity, parental characteristics, childhood temperament, sociability, cholesterol levels, and stress. It might also surprise you to know that the old are less depressed than the general population, Vaillant reports, and the majority don’t suffer from incapacitating illness till the one that gets them for good.

That boat can give you a devastatingly beautiful trip on exquisite and enchanting seas. Age brilliantly? Yes! Let the band play on, with vigor and alacrity and joy, till the whole thing goes under with a shudder and a sigh, slipping valiantly into the deep.

Age: The Real Tip-Offs

There are about 35 of us beauty editors at a presentation of a company's new product. I'm new, too, new to the job of beauty editor, just learning the ropes. Most of the women are lovely, sparkling, and girlish; only a few of us have seen 40 (and fewer yet, like me, are peering fondly back). A convivial young man standing at a wooden podium welcomes us. "Thank you all for coming," he says, sparkling a little himself. "I have a question for you," he says. He leans against the podium professorially: "Can anyone tell me, what are the four signs of aging?"

I generally do well in classroom situations, and greenhorn though l am, l know the answer he's looking for: fine lines, sagging skin, excessive dryness, etc. But I'm reluctant to raise my hand. Because if l do, and l give him the answer I believe is true. I'm afraid l might put a blight on the magazine l love and now represent. What if the young man is offended because I'm not playing along? So l sit on my hands and regretting, regretting, bite my tongue.

Today, however—two years of experience and a lifetime of antiaging presentations later— is a different story. Ask the question again; in fact, I dare you to ask the question. Because now l am very sure there is only one right answer, and it is my happy responsibility to give it.

What are the four signs of aging?

They are Wisdom, Confidence, Character, and Strength.

Look for them not with dismay, but with hope.

The Lady Vanishes

Valerie Monroe was used to being seen—and appreciated. Until she reached an age when the glances stopped. Then what? An invisible woman begins her search for a new identity.

A few months ago, I spent an afternoon helping out an art dealer friend at a print fair. At a table in front of his display, I sat on one side of him while his assistant sat on the other; we greeted prospective buyers as they walked by. "Hi there!" I would say with warmth and (what I thought was) a touch of modest charm when I saw one coming. Time and again, from the men, I got a limp, dismissive "hi" in response, occasionally a nod. It wasn't the Whistlers or the Chagalls that were diverting the art lovers' attention; it was my friend's lovely assistant. She wasn't flashy or glamorous; but she had a smooth, milky, 20-something complexion and the sweet, expectant, wide-eyed look of youth. Thirty years ago, I might have been her.

Today, however, I'm 58 and I look it, by which I mean that I haven't had any work done to make me appear younger. I'm trying to get down with the aging thing, to accept it—at least till I've decided that I can't. Almost every morning I discover some other small reminder that I am growing older: an age spot, another wrinkle or wisp of gray in my (thinning) brows.

If you're going through this, you already know that watching your face mature is not the most gratifying spectator sport—because no matter how constantly or enthusiastically you root for the home team, eventually age will win the game. Which is a good way to think about it, because the bottom line is that the process of aging involves a certain amount of loss. And what I discovered at that art fair is that if you have benefited from the currency of your looks, when that currency loses its value, you can end up feeling pretty bankrupt. Entering a room of mixed company—a meeting, a party—or walking down a crowded street, I've learned to expect that I'll attract a little attention. I don't mean that people stop in their tracks, open-mouthed, and stare (as they have when I've walked down the street with my 6 2, striking young niece), but I've been banking on appreciative glances for a long time. They make me feel pretty, which makes me feel happy. Not in the way, certainly, that motherhood has made me happy, or my work, but there is a small feeling of satisfaction attached to receiving these looks; it's as if, at least on the face of it, I know how to do this female thing well.

So I guess it shouldn't have been shocking to me how difficult it was to be distinctly ignored. I hadn't been aware that the glances I'd been accustomed to had been falling off. That afternoon, I felt as if I had been stripped of all color and was the only gray-and-white figure in a richly tinted painting. I was Marion Kerby, one of the ghosts in Topper, all dressed up and nowhere to...be seen.

Becoming invisible is disconcerting enough. But I am beginning to feel obsolete differently, too, maybe more profoundly. I'm almost embarrassed to admit how much I still miss the fundamental, quotidian tug of a child's needs, the grounding responsibilities of parenthood. When I was actively child-rearing, my life had a purposefulness I grieve to this day. My son, at 25, now lives away from my home and is stunningly, happily independent. Which is exactly what I'd always aimed for in raising him, so I am deeply grateful. I just didn't know that along with a joyful sense of accomplishment, I would feel, in some persistent, incontrovertible way, useless. Not pandemically useless; I work, I'm productive in the ways one has to be in order to fall into the category of functioning adult, but the comforting sense of knowing my purpose from the moment I open my eyes in the morning has been replaced with a kind of disquiet. I have, if I'm lucky, a third of my life left. How am I going to spend it so that I feel the fulfillment I felt in the previous third? What can I do that matters?

And here is where the issues of being ignored and feeling obsolete converge. The art fair men—unconsciously, surely—disregarded me in part because I'm no longer fertile, unable to provide them with proof that they are still capable of reproducing. The emotional impact of having it so ungraciously pointed out that I have outlived my reproductive value was like having a bucket of cold water thrown at my face—or, rather, a cold grave opened before me. Because that means, in a Darwinian sense at least, I'm over.

Gentlemen, I feel your pain.

The thing is, though my production line has shut down, the factory is still very much open. And I believe there is more work to be done before it closes for good.

The psychologist Erik Erikson suggests that there are many ways to express what he calls "generativity"—the need to produce something that contributes to the betterment of society, which not only helps others but makes us feel more content as we get older. That will be my focus as I march, largely invisible, into my future.

I can tell you this: Even if you don't see me, you will know that I am here.

Beauty and the Bitch

You know that little voice that relentlessly berates you whenever you look in the mirror, the one that makes you wince every time your appearance falls short of some impossible ideal? Enough! Valerie Monroe cuts a tyrant down to size.

“My God, you are beautiful.” Has anyone ever said that to you? Yes? No? Whatever: Imagine it now. Imagine someone looking into your eyes and saying, “My God, my God, you are beautiful.” What would it mean to hear that? Would it mean that you had the face of the Madonna? The body of Madonna? Would it mean that the person who was saying it was delusional? Or in love?

One morning not long ago at the O magazine offices, 14 of us sat around the heavy conference room table, another 12 of us in a second circle of chairs behind the first. The subject was beauty. We’re a pretty vocal group, mostly outspoken and forthright, and by anyone’s standards, we are also a pretty pretty group—even (I think) a pretty beautiful group. To wit, Beauty A: luxuriously thick, dark curls; a clear, pink complexion; deep chocolate brown eyes; delicate nose; full, generous mouth. Beauty B: a towhead; fair, poreless skin; sky blue eyes; Cupid’s bow, ruby lips. Beauty C: a life-size Barbie doll, hourglass figure; huge brown eyes; ski-jump nose; perfect teeth. Beauty D...well, you get the idea. Each of these women is asked whether, in her heart, she knows she’s beautiful. And beauty after beauty reveals her secret: Me, beautiful? Never! I’m plain! Even, sometimes, ugly! Don’t look at me without makeup! One of the women, with creamy skin, wild dark hair, blue eyes, an athletic build, and ajo March personality—which is to say she plunges ahead in most endeavors with great, astonishing aplomb—claps her hands smartly over her ears at the mere suggestion that she might be even the slightest, tiniest bit attractive.

And so there we all were, staring at one another, stupefied, and asking, “How can you not see how beautiful you are? Where is your critical voice coming from?”

We got an answer of downright mythical proportion from Beauty A, who long considered her luxuriously thick, dark curls the bane of her existence, a glaring, unfortunate beacon of her awkward unruliness, her inability to fit in with the prevailing ideal of womanhood. She traces her discomfort to her grandmother, a grande dame whose rigid notions about beauty were deeply entrenched in Southern tradition. There was only one way for a woman to look—discreet, well groomed, polished, ladylike. Stray from it in anyway (which included wild curls) and you became a kind of pariah, judged to be unmannered, slothful, poorly raised, and maybe loose; conforming was away to hide anything that might threaten your station in society.

Her grandmother was a forceful woman whose notions snaked perniciously through the generations, gripping Beauty A and her sisters. It was only recently that they discovered the root of her abnegation and, consequently, their own. As a young woman, their grandmother, considered quite a beauty in her day, had descended the staircase in her family home dressed and made-up for a big dance, only to be met by her own grandmother in the parlor. “Go back upstairs and fix yourself!” her grandmother had cried. “You look awful!” Bad enough. How had she transgressed? Makeup overdone? Dress too revealing? A hair out of place? She could have asked her grandmother. But how would the old woman have known? Her grandmother was blind. Which begs the question, What was she reacting to? What deep, unsettling fear could have inspired such an outburst? Whatever it was, the fact remains that five generations later Beauty A still struggles over her lovely mess of curls.

Shaking our heads, we asked ourselves the most important question: How can we end this deadening, compulsive self-criticism and begin to talk to ourselves about beauty in a kinder, more compassionate and appreciative, less punishing way?

If you stop to think about it—and let’s do that, right now—you’ll realize that most of the messages we get about the way we look have to do with denial and withholding (avoid looking older, eat less) and imperfection and loss (conceal your flaws, regain your firm complexion). Can you recall the last thing you read or heard that suggested you celebrate or even acknowledge the positive aspects of the way you look? (I can; it’s “Here’s Looking at You, Kid!” by Martha Beck, on page 266, but stay with me for a minute.) Instead, we’re bombarded with images of the young, the skinny, the oversexualized, the computer idealized. The effect on our self-image and self-esteem is even deeper than you might imagine. Psychologists call it normative discontent: It’s considered normal for women to be unhappy with the way we look. Follow this line of thinking: If it’s normal, then for us to fulfill our role as women, we’re supposed to be displeased with our appearance. Does this resonate with you? Are you afraid to admit that—one day, for a few minutes, stepping out of the shower or into the bath—you actually do look okay, or maybe even (God forbid) pretty good?

From the moment we appear in the mirror in the morning, we are face-to-face with our inner critic—call her Judge Beauty—the one who presides over the viciously unforgiving Court of Egregious Imperfections. The interrogation begins: Are you thin enough? Is your complexion bright enough? Your bottom firm enough? Smile white enough? Flair shiny enough? Are your lips too thin or too full? Your eyes too small? Your nose too big? And what’s your defense? Haven’t been taking care of yourself? Not paying attention? Or saddest of all, were you simply born that way? This line of questioning is supported by a constant stream of messages nearly everywhere we look that we could be more attractive if only we wore this or drove that, ate this and not that. In ways subtle and not so subtle, culture teaches us to look cruelly upon ourselves. We’re raised to pay attention to these messages—improvement being an essential element of the American dream— and to take them to heart. Ask yourself: Do you equate being pretty with being happy? Have you ever thought that if you were prettier, you might be happier?

In case you’re thinking that this kind of severe self-judgment isn’t all that common, here is a first peek at some interesting statistics from a soon-to-be released global study commissioned by Dove, the company that created a sensation with photographs of real women of different sizes in its Campaign for Real Beauty:

■ Only 7 percent of American women (15 to 64) have never been concerned about their overall physical appearance.

■ Ninety-two percent of American women (15 to 64) want to change some aspect of their physical appearance, mostly body weight and shape.

■ Almost two-thirds of American women agree that when they feel bad about themselves, it usually has to do with their looks or weight.

■ Living with beauty ideals leads almost seven in ten women globally to withdraw from important, self-actualizing activities, such as going to school or work or a job interview, because they feel bad about their looks.

These feelings of inadequacy, the striving for perfection, the competing, the comparing—with others or with younger versions of ourselves—is all a fool’s game. No one ever wins, not even the most conventionally beautiful. As Rita Freedman, PhD, clinical psychologist and author of Bodylove, points out, if you think you’re not pretty, you spend your life regretting that, and if you think you are, you spend your life in fear of losing your looks. Then one day, you do lose them. (You want something to cry about? We’ll give you something to cry about!)

We’re not supposed to be excessively concerned with the way we look; it’s unseemly, prideful, immodest, vain. Vanity stems from competitiveness, says Freedman; it even suggests evil impulses (Mirror, mirror, on the wall...). But here’s the rub: As women our sense of self is inextricably bound up in our appearance, and so we tread a very fine line between concern and overconcern or obsession. Freedman reports that in a classic research study, psychotherapists were asked to rate the personality traits of a healthy woman, a healthy man, and a healthy person. “Preoccupation with appearance” (vanity) was rated normal for a healthy woman but abnormal for a healthy man and for healthy people. That leaves us stuck in a damned if we do, damned if we don’t dilemma, she points out: aware that we’re judged by our attractiveness but ashamed to admit how deeply we value looking good, because that would mean we’re...vain.

That seems like a lot of bad news. But there is a slight trend toward a more forgiving attitude: the Dove advertisements, showing robust women comfortable in their bodies; Nike ads suggesting that we focus on what our bodies can do rather than on how they look. These messages can remind us that we need to see ourselves through kinder eyes. Maybe you’ve already learned how to do that, if you’ve been looked at kindly—by a parent, a friend, or a lover. If not, you can learn it now. A while ago I discovered a photo of a little girl at age 5 or 6, not at all a pretty child. Her demeanor is more Alfred E. Neuman than anything else. Her smile is wide and real, but what you notice most—after her seismic optimism—is that she has only one tooth on the top, one huge, white tooth, and it’s taking a detour, too, a hard right when it should be going straight. Even so, she thinks she is a fine-looking child, and who (she wonders) in their right mind wouldn’t agree? She’s vulnerable, open, engaged with the world, a lively (if ingenuous) presence. When I catch a glimpse of myself on a bad day, not looking the way I wish, rather than turn away from my reflection in disappointment or even disgust, I keep looking till I can see that child, that happy girl who knew that, in spite of her freckles and skinny arms and foolish, scrappy smile, she was beautiful enough. Can you see that innocent kid in yourself? Once you do, you will see her in everyone. Because real beauty isn’t about symmetry or weight or makeup; it’s about looking life right in the face and seeing all its magnificence reflected in your own.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Inner Beauty: The Shining

You know it when you see it, but it's difficult to describe: inner beauty. It transcends the impression of a woman's physical traits. Feature by feature there may be nothing special about her—she may even be plain—but something about her attracts you in the most profound way. Something radiates from within.

What is it?

"You're responding to empathy, compassion, an openness to others," says Matthieu Ricard, former genetic researcher, now Buddhist monk and author of Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life's Most important Skill (noted in Reading Room, page 218). "You see it on someone's face when she feels in harmony with our deepest nature as human beings, which is basically peaceful and loving."

But how does that harmony manifest itself physically? Through subtle expressions, says Ricard, which we pick up both consciously and unconsciously. Hundreds of almost imperceptible muscular movements constantly communicate our feelings. Think of how a classically beautiful face changes when it's transformed by contempt; less beautiful, right? Maybe even ugly? Unconditional love transforms a face, too, says Ricard. We identify with that look, it brings up in us a yearning to be loved and to be loving; and it reminds us of the best we can be, which we may have forgotten or sublimated. And so, inspired, we wind up looking out at the world through more loving eyes, passing the harmony along. That's the thing about inner beauty: Unlike physical beauty, which grabs the spotlight for itself, inner beauty shines on everyone, catching them, holding them in its embrace, making them more beautiful, too.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Stop Right There!

Five Things You Should Never Do If You Want to Feel Beautiful

1. Don't use a magnifying mirror, except for tweezing your brows. If you've ever studied your face in one, you probably don't need an explanation as to why it's not a great idea. But Francesca Fusco, MD, assistant clinical professor of dermatology at Mt. Sinai Medical Center in New York City, offers a few good reasons. A magnifier will make you focus on things that can't be seen with the naked eye, so what's the point of knowing they're there? Also, because everything on your face looks wildly out of proportion in a magnifying mirror, you may get inappropriate ideas about what you actually need. For example, a woman focusing on the little lines above her upper lip might say "Supersize me" to the doctor holding the collagen. (And that, O Best Beloved, is how the lady got her trout lips.)

2. Don't use fluorescent lightbulbs around the bathroom mirror. They emit a flat, white, harsh light that makes everyone look as if she were sick. Better: halogen bulbs with a glass frost filter—MR16 are good ones, says New York City lighting designer Ira Levy, because they emit a clean, even light. In general, the prettiest, most flattering light is warm, incandescent, and dimmable.

3. Don't participate in any kind of skin analysis that involves a machine. By using a probe on your face, these devices (often found in department stores) measure pore size, oil levels, dryness, the number and depth of wrinkles, etc., and give you a printed readout, including bar graphs, on the condition of your skin. For some reason—could it have to do with marketing?—the news is never "Nothing could possibly enhance your flawless complexion."

4. Avoid being lit from below—unless you want to scare the heck out of your kids. You know those little canisters of lights that sit on the floor and shine up into a room? Move away from them. Light, in nature, comes from above, and so we're accustomed to seeing the world this way, points out Stephen Dantzig, author of Lighting Techniques for Fashion and Glamour Photography. But light that's shining directly down on your face can be equally unflattering (which is why it's imperative to inform the paparazzi that you must not be photographed outside at high noon on a sunny day). Balanced lighting—for example, one ceiling light directly centered over the bathroom sink and one on either side—will eliminate unflattering shadows, says Levy.

5. Don't compare yourself to women you see in magazines or movies. If you had 15 handlers making sure your hair and makeup were perfect, you'd look pretty glamorous, too.

The Revolution Starts Here!

Everywhere we turn, there are images of gorgeous women, constant reproaches to the reality of us, with our real bodies and un-Photoshoppedflaws. We’re not buying it anymore. We’re tackling the critics—from the parents and teachers who favor the prettiest children to look-ist employers to the most hurtful of all, that nasty, catty girl who lives right behind our eyes.

Not long ago, I sat in my office, chatting with a friend. “I want to talk to you about your face,” I said. “Oh my God,” she said, looking stricken. “Do I need a facelift?” (I forget that people think I have a right to be openly critical of their appearance because I’m a beauty editor.) No, no, I said; I only wanted to know what she saw when she looked in the mirror.

“I like my face now,” said this woman, a classically beautiful 38-year-old, very polished and buttoned-up, as neat and perfectly composed as a Modigliani painting. “But I was adopted from Korea when I was 3, and I grew up in a predominantly white community in a small Midwestern city, where there weren’t many other people who looked like me. I was teased, called names; I basically spent my entire childhood being made fun of because of my face.” She said this calmly and, recollecting, was silent for a moment. I waited for her to go on. But when she tried to speak again, she burst into tears. And there she sat in the chair across from my desk, crying hard for several minutes. I offered her a handful of tissues while she apologized for breaking down. This woman is so self-controlled, I’ve never even seen her yawn. Finally, she said, “I didn’t realize how fragile I still am about this. I wanted to do anything I could not to look Asian, because it set me apart,” said my friend. “You know, I had some really bad perms. But when I got to college, where there were a mix of ethnicities, the stigma of my face just disappeared. There were people who appreciated my beauty, and so I began to see myself the way they did.” In other words, she made the liberating discovery that there was nothing wrong with her face, and something wrong with the culture of her hometown.

Though race hadn’t been an issue for me, I, too, was teased and called names because of my appearance (suffice it to say I spent several difficult years as a grasshopper before slowly metamorphosing into a normal-looking teenager). And I, too, did everything I could to try to fit in with my peers, including dying my dark hair blonde and tweezing my brows into a shape that might generously be called unnatural. In away, we’re all trying to “pass,” minimizing with cosmetics (or, in the extreme, surgery) what deviates from the cultural ideal, playing up what conforms, says Rita Freedman, PhD, a clinical psychologist and author of the 1986 book Beauty Bound. “It’s what you project onto the reflection in the mirror that determines how you evaluate it,” she says.

I spoke to several other women I had assumed—because they are all accomplished and beautiful—felt fine about their face. One, thinking of a photograph of herself as a 13-year-old, teared up as she remembered the depth of her self-revulsion. (This time I was ready with the tissues.) Another tried determinedly to convince me that she was a truly ugly person till her 20s, at which point, she said, she was briefly attractive before becoming merely plain in her 30s. A third told me she couldn’t wait to get glasses so that she could hide the gigantic bump on her nose (a gigantic bump that was invisible to me). And a fourth—stunning, without a stitch of makeup—said that she knew she wasn’t horribly disfigured, but avoided looking at her face in the mirror whenever possible (as if she were...horribly disfigured).

Though the cultural ideal has broadened to include more diversity, it remains an ideal, setting an unrealistic standard by which we all, consciously or not, judge and are judged.

The painful truth is that physically attractive people get rewarded in all kinds of ways: As children they’re usually disciplined less harshly and favored in the classroom; as adults they tend to have better-paying jobs in higher-level positions than their less attractive counterparts, writes Gordon L. Patzer, PhD, in his recently published book, Looks: Why They Matter More Than Ton Ever Imagined. Which, frankly, stinks.

It stinks even if you’re gorgeous, by cultural standards. Valuable as it is, gorgeous is not a good stock to invest in. It has a completely predictable payout. No matter what you do, how well you take care of yourself, how much surgery you submit to, one day you are going to lose everything on your investment. You know this, I know this. Even so, we buy into the beauty rules, colluding with a culture that makes us feel inadequate, whipping ourselves when we come up short. Which makes us—come to think of it—part of the problem.

What if, instead of colluding, we traded cruelty for kindness? What if we started a revolution, if each one of us took a vow to catch ourselves scowling or sneering at our imperfections—and simply stop? If we noticed every time we had a nasty, hostile response to someone else’s appearance—and simply stopped? Think about who your inner critic is: She’s the mean girl who doesn’t want you in her club, the one who takes pleasure in pointing out all the ways you don’t measure up. Her trump card is your fear, fear that you will never measure up, that you are, bottom line, unlovable. Every moment you spend calculating your imperfections (or anyone else’s), you are taking her side.

This is a call to arms. A call to be gentle, to be forgiving, to be generous with yourself. The next time you look into the mirror, try to let go of the story line that says you’re too fat or too sallow, too ashy or too old, your eyes are too small or your nose too big; just look into the mirror and see your face. When the criticism drops away, what you will see then is just you, without judgment, and that is the first step toward transforming your experience of the world.

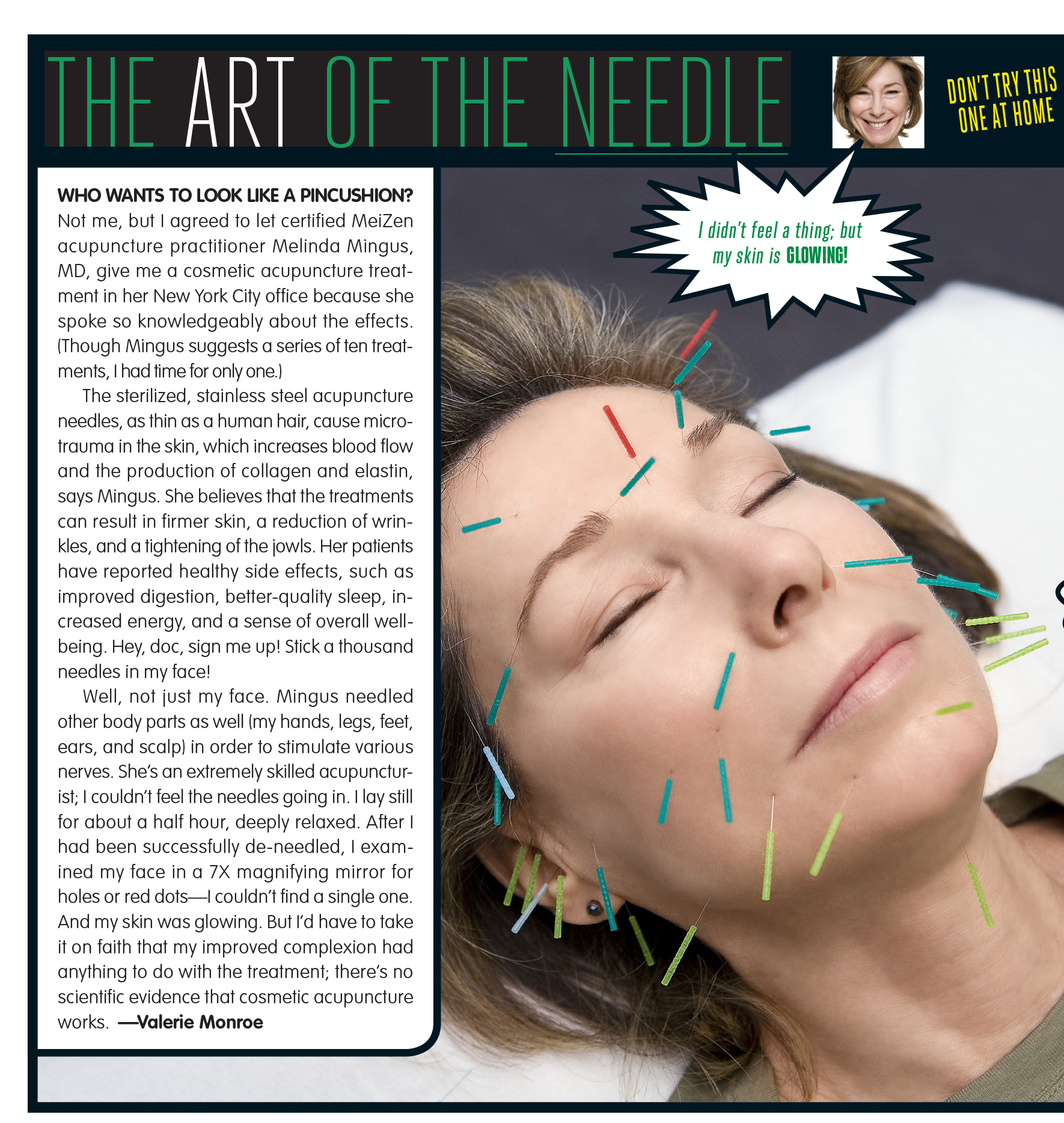

The Art of the Needle

Who wants to look like a pincushion? Not me, but I agreed to let certified MeiZen acupuncture practitioner Melinda Mingus, MD, give me a cosmetic acupuncture treatment in her New York City office because she spoke so knowledgeably about the effects. (Though Mingus suggests a series of ten treatments, I had time for only one.)

The sterilized, stainless steel acupuncture needles, as thin as a human hair, cause microtrauma in the skin, which increases blood flow and the production of collagen and elastin, says Mingus. She believes that the treatments can result in firmer skin, a reduction of wrinkles, and a tightening of the jowls. Her patients have reported healthy side effects, such as improved digestion, better-quality sleep, increased energy, and a sense of overall well-being. Hey, doc, sign me up! Stick a thousand needles in my face!

Well, not just my face. Mingus needled other body parts as well (my hands, legs, feet, ears, and scalp) in order to stimulate various nerves. She's an extremely skilled acupuncturist; I couldn't feel the needles going in. I lay still for about a half hour, deeply relaxed. After I had been successfully de-needled, I examined my face in a 7X magnifying mirror for holes or red dots—I couldn't find a single one. And my skin was glowing. But I'd have to take it on faith that my improved complexion had anything to do with the treatment; there's no scientific evidence that cosmetic acupuncture works.

There Will Be Blood

A facial that really gets under your skin.

When you tell people you’re going to have your face poked all over with tiny needles, you get two responses: “Yech!” and then, “Why?”

I’ll tell you why. I want the smoothest, freshest-looking, glowiest skin—and to that end, many dermatologists suggest microneedling, a process in which a small device embedded with a cluster of sterile, retractable needles is pressed all over the face, causing “micro-injuries.” The skin rushes to heal those injuries with new collagen and elastin, which, if you’re my age (66), are literally face-saving; they help keep it from looking like all the stuffing’s been pulled out of it.

There are at-home kits, but doctors aren’t fond of them because they say the needling typically doesn’t go deep enough to get appreciable results—and because infection is possible. So I made an appointment with New York City dermatologist Cheryl Karcher, MD, who uses the EndyMed Intensif microneedle device. The Intensif also emits pulses of radio-frequency energy to further tighten skin and minimize pores. In the equivalent of a skincare trifecta, Karcher suggested I increase the benefits by rubbing into the “micro-injuries” 6 milliliters of my own platelet-rich plasma, which she extracted from a vial of my blood drawn just before the Intensif procedure. (If you’ve read about the “vampire facial,” you’ve probably seen photos of famous faces smeared with blood. On me, Karcher used only the yellowish plasma because it contains beneficial growth factors.) Numbing cream is applied pre-procedure; still, I have two words for you: staple gun. Karcher moved the device over my face in increments of about an inch as she released the needles. It really hurt, especially around my lips and eyes. The plasma, warm and sticky, is mostly absorbed during the minutes after the needling, and though Karcher said I could rinse it off, for good measure I left it on all day.

For about 24 hours, I was very pink, with one small red dot on my forehead, and for several days, my skin peeled a bit. By the end of the next week, my cheeks looked smoother. Over a month or so, as the collagen and elastin regeneration continues, I should see more glowiness and a little tightening, says Karcher. Which seems well worth the yech and ouch to me.

A Shot At Gorgeous

Millions of women are looking remarkably fresh and rested thanks to tiny injections of a botulinum toxin. Why wasn’t Valerie Monroe one of them? O’s beauty director develops a few new worry lines.

It’s not like my face is that symmetrical or anything—no more symmetrical than yours, I bet—but the idea of doing something to it that even in the slightest way might increase the chance that it could become lopsided? That put the fear of God into me. So I canceled my first appointment with a New York dermatologist who had offered to shoot me up with Botox when I told her I was considering trying it for this story. I called her specifically because I know she has used Botox on herself for years, and she looks fantastic, by which I mean she can smile and frown